Lessons Learned from Our First AI Legal Research Class

I'm Emily, and I’m one of VAILL’s collaborators, a law librarian, and a self-identified long-winded human. The last part makes for a long post this week, but bear with me, because I think you’ll find it interesting. I'm sharing insights from VAILL’s AI Augmented Legal Research course launched in Spring 2025 for Vanderbilt Law students. We launched this course around the same time a few other schools launched theirs, but I think we did a few things differently, and I’m excited to share that. Now that summer is in full swing, I've had time to really reflect on what worked, what surprised me, and what I think it reveals about how our students will responsibly and critically use AI in their future practice.

And, for those of you who are interested in the data and don’t want to go on an exciting journey into course design and development: you can jump to the end, TLDR: Key Insights from the Students.

One last plug before we get started, we launched the VAILL website this week: https://www.ailawlab.org/ This is where you can learn about all the cool work we do, not just teaching!

How LAW-7015 Came to Be

When VAILL co-founder Mark Williams first proposed co-teaching an AI legal research class, our goals were twofold:

We’d spend the entire class diving deep into AI research tools (rather than just a week in our general AI and Law class); and

Each student creates a custom GPT of their interest for their capstone project.

Back in Spring 2024, when the class was pitched to Vanderbilt faculty, this seemed ambitious but do-able. With the class being one credit and pass-fail, we had flexibility to experiment and see if this would work (and the built-in forgiveness that comes with being one of the firsts to have a course like this).

As AI tools have rapidly evolved over the last year, creating custom GPTs have become almost too easy. Students were building custom GPTs that acted as functional, albeit unpolished, class tutors and research assistants. Not that the class’s crowning achievement needed to be hard or time-consuming, but we definitely wanted students to experience something ‘different’ in this class. If they could do it on their own, why would they need our class?

So, back to the drawing board for one of our goals, which, if you’ve ever taught a class, you know well that deciding to change the class’s final assessment is a big deal in and of itself. But, when we launched the course with 32 students enrolled, the course ended up being different in more ways than just that. As VAILL has grown, Mark’s expertise was needed elsewhere, leaving me to redesign the course solo. I’d taught legal research before, but building a brand new class around a topic that changes daily? That felt daunting.

Course Design Mantra? Philosophy?

One thing I did (and still do) know: I want to teach classes that I would have liked taking as a student. That sounds obvious, right? No one wants to teach a course they don’t like or wouldn’t take, but that’s how it shakes out sometimes. With creative control in this class, I wanted to make it something that I wished I’d taken more of and gotten to experience in law school. How could this class become something that would ease the anxiety of the transition to practice?1 I wanted this class to emulate what students would experience in practice as much as was feasible (and believable). Too, rather than simply teaching them how to use AI tools, I wanted students to develop informed perspectives on when and how these tools could enhance their work. I wanted to give them an idea of what worked for them and their practice, not just a general idea of what tools were good (or advertising themselves as such) for a lawyerly skill.

I knew most of the students would be 3Ls: they might not have had any legal research instruction since 1L, and they likely didn’t have any formal AI instruction. Vanderbilt’s 1Ls started receiving AI instruction as part of their legal research course in the Fall of 2023, so our current 3Ls just missed it. I wanted them to experience the contrast between traditional legal research methods and AI-augmented approaches in a controlled, pedagogical environment, but also take away something that they could quick adapt and use when they entered practice in a few short months. These students would be entering practice in months, with partners expecting them to understand what AI tools could offer the firm. I wanted our graduates to confidently engage in those conversations and point to concrete experience.

So, there’s another challenge: how could this class simulate what they’d actually experience in practice while giving them something genuinely useful for their careers? And, that would cover all the good foundational things about AI and legal research… In seven weeks... No sweat!

Inside the Classroom

The seven-week course was set up to mirror different aspects of the capstone project, starting with baseline AI knowledge and moving through primary law research, secondary sources, research planning, and drafting. We also brought in guest speakers, including law firm librarians who shared practical research tips and data science experts who explained the ‘hard parts’ of AI and expanded the definition of “AI” beyond just generative AI.

We started with an introductory AI class to make sure everyone had the same baseline. In the next two weeks, we covered primary law research, and the remaining weeks, we picked up secondary sources, research planning, and drafting.

I used a pre-class survey to get an idea of what students already knew and to figure out what tools students already were familiar with or had used already. Based on the results, I was able to briefly cover some topics that might have taken up more class time, but looking back and moving forward, I’d spend more time in the introductory class explaining foundational concepts. Most students had at least tried some AI tool and done so in connection with some sort of academic or professional legal work, but I think there was more foundational material I could have provided that would have helped them feel more comfortable.

When it came to the actual capstone project, I’d spent much of the winter break figuring out how to best fit the scope of the class with their ultimate assessment. I’d ruled out the custom GPT idea and similar ideas about creating other custom tools: they just weren’t challenging enough in a meaningful way for this course. I thought about the types of group projects we do in the classic Advanced Legal Research classes, but I didn’t like putting students into teams and having them work together on one research question either. It would be too easy for one experienced student to dictate what the rest of the group did, limiting what the others felt comfortable experimenting with or sharing.2

Ultimately, I landed on something that I was excited about: a comparative research experiment that closely simulated real practice conditions. Each student received a unique research question across different areas of law—either in areas they were interested in or, like real practice, whatever a partner needed help with and didn’t have the time or interest to do. Each research question was crafted to guarantee at least enough complexity that AI tools would be tested beyond simple information retrieval and would require students to wrestle with some nuance.3

Some questions were built on real scenarios, and a big thank you to all my friends in practice who contributed ideas. Some questions were based on headlines I’d seen, and some were just completely made up. I found ChatGPT to be a nice helper here, at least to flesh out some of the questions and add detail.

The Capstone Experiement

Students first tackled their research questions using only traditional methods. This is what I was thinking of as the legal research equivalent of establishing a baseline. They were prohibited from using generative AI tools for any aspect of their process at this stage. No Westlaw Co-Counsel or Lexis Protege to start their in-depth legal research, but also no ChatGPT or Claude to generate search strings or outline the topic.

They received their research question on a Friday afternoon, as I was literally walking out the door for a nice weekend away from work (much like a law firm partner dropping by your office on a Friday afternoon to ask a favor; ask me how I know!). They had the weekend to research their question and compile their findings to share in a ‘partner meeting,’ which took place the following week. They were then free to use any AI tools at their disposal to research the same question again.

I asked students to track their time throughout both phases, allowing for a real comparison of what they spent their time on, while also asking them to practice time keeping. The instructions emphasized that there was no “right” approach or expected outcome: the goal was self-discovery through experimentation.

They shared their AI-findings in a five-minute-long presentation to their classmates. I asked students to treat the presentations like a task force meeting. I wanted them to imagine that they’ve been appointed to the firm’s AI task force, and they would be quickly sharing their “use case,” while listening to others about what worked (or didn’t work) in their practice area.

After all the presentations were concluded, students drafted a reflection paper on what their capstone experience was like. They could use any tool to help them draft the reflection paper too: many students took advantage of this and used the course syllabus, the capstone guidance documentation, their research, any partner meeting notes, and their presentation materials to create their reflection paper. The results were outstanding, with every student turning in something that was polished and on point.

In designing the capstone, I wanted to create a space for students to develop their own conclusions about these tools through direct experience, rather than theoretical discussion. “There is no ‘right’ way to go about this process,” I told them. “You can experiment with one tool or use a bunch of them. The more you experiment, the more you’ll get out of the experience.” I didn’t require them to use a specific tool or to use a set number of tools. The best way to learn these tools is to use them: isn’t that what AI experts and educators keep telling us? That’s what this project was about: try something, see what it does, get messy, fail, succeed, etc. and so forth. Most students embraced this spirit and tried more than one tool, and all of the students used at least one tool for more than one skill.

Results: A Sophisticated Workflow with Critical Judgment Intact

The overwhelming consensus (30 of 32 students) favored a hybrid approach combining AI and traditional research methods. Rather than seeing AI as a wholesale replacement for conventional legal research, they viewed it as enhancing specific aspects of their process. One student described the experience as “bouncing ideas off a research assistant” rather than receiving static reports, highlighting the iterative, conversational nature of working with these tools.

Every student recognized that this wasn’t a 1:1 situation with their future roles in practice: they knew they couldn’t use the tools the exact same way in practice as they did in their class. What was especially exciting about this is that they independently all recognized one of the big tenets of what we preach at VAILL: the tools change, so the process of how you evaluate and employ them is what is truly valuable. They recognized and articulated that it wasn’t “X tool can do Y” that was important — it was more that “doing Y could be improved with tools like X.” VAILL tries to make this clear not only to students, but also the attorneys and other community members we interact with, but it is nice to see that students are picking up on it! (They are listening!)

Ultimately, this is what really surprised me about students in this class, and I think it bodes well for the future of legal work. My students quickly identified the unique strengths of different tools and developed sophisticated, thoughtful multi-tool workflows. They didn’t use just one tool for one thing. They weren’t just buying what these tools were selling. They didn’t shy away from being critical.

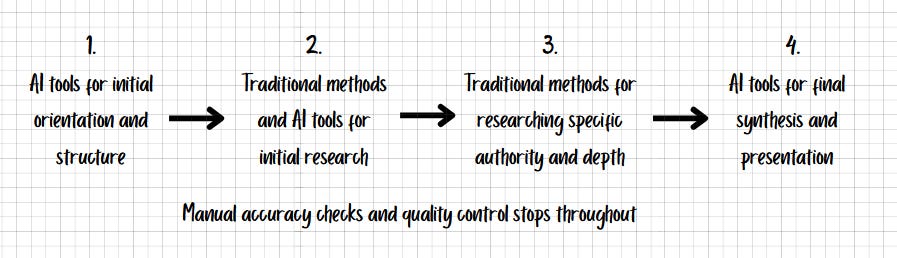

With this in mind, each student developed a similar workflow with plenty of their own built-in verification points:

Students understood that the tools couldn’t do the job for them. They weren’t just along for the ride and taking these tools at face value! Even if they were working in an unfamiliar area of law for their research question, they still felt comfortable assessing source quality and using their own judgment to make sure their work product was both accurate and on point.

Too, they all easily identified several important limitations of these tools that we all know too well:

The need for verification of AI-generated content, especially citations;

Occasional hallucinations or fabricated case details;

Difficulty with jurisdiction-specific research; and

Limited ability with nuanced legal analysis.

We hear a lot about the issues practicing attorneys have with using AI, and we’re all familiar with the mistakes being made in practice. Our students know this too! They understood the bigger picture. Fake cases and hallucinated information weren’t just academic concerns for them— they recognized the professional and ethical implications of relying on potentially incorrect information.

Looking Forward (Next spring, here we come)

We can see something in this first iteration of the class that will still be true in a year, five years, and so forth: when law students are given freedom to explore AI tools, they will develop thoughtful approaches that leverage technology while maintaining professional judgment. They don’t need to be protected from AI tools: they need opportunities to experiment with them in controlled environments that mirror real practice pressures. This isn’t just true for Vanderbilt students; this is true for students at other law schools as well.

Students are ready for this level of experimentation. They’re looking for and listening to our guidance about critical evaluation, but they’re also coming up with their own ideas about how to evaluate tools for their use. Law students are capable of and are actively developing the kind of hybrid workflows that will define their legal practice. We should give them the space to try in the classroom, because they are smart, curious, and ready to take on the challenge.

And that’s really the bottom line: the kids know what they’re doing! And the profession should be excited about that. When given freedom to experiment, law students don't see AI as a replacement for traditional legal research: they develop sophisticated hybrid workflows that leverage the strengths of both approaches while maintaining critical judgment about accuracy and limitations. That’s the right approach.

TLDR: Key Insights from the Students

For those of you that just want the data, here you go! I did a quick analysis of their reflection papers, and the “big themes” I was able to pull out, with the help of my good friend, Claude:

Most Popular Tools for Experimenting:

ChatGPT led by a significant margin (22 mentions).

Claude (16 mentions) and Midpage (14 mentions) formed a second tier.

Lexis AI/Protégé (11) and Westlaw AI-Assisted Research/CoCounsel (9) rounded out the top five.

Areas where students found AI particularly helpful included initial research orientation and scoping, organizing and synthesizing information from multiple sources, preparing presentations and drafting final documents, and generating Boolean search strings for traditional databases.

Tool Specialization:

ChatGPT showed strong versatility across all functions.

Claude excelled particularly in drafting tasks, where students valued its ability to match their writing style.

Midpage was primarily used for research experimentation, the “just to see what else is out there” option.

Notebook LM was stronger for organizing initial research to get an idea of the position students would advocate. They felt Notebook LM did a better job than their non-AI ways of organizing and was the strongest of all the tools in organizing.

Most Significant Strengths:

Speed/Efficiency (28 students).

Students felt they could achieve the same or comparable results as traditional research with their hybrid approach but in much less time.

Organization capabilities (24 students).

Students felt their research was better planned and organized when using generic/basic AI tools to help them structure their output.

Summarization skills (22 students).

Students identified the summarization skills of all tools as the main major time saver. They quickly identified primary materials that were more or less relevant to their search, almost using these tools as their own topic-specific headnote system.

Presentation preparation (18 students).

Preparing their results to share often took up most of their time, and many students recognized that this time would likely not count toward their billable hour requirement. Students recognized that these tools excelled at getting them ready for the meetings or presentations in a quick and thorough way.

Search term generation (14 students).

Especially in areas where they didn’t have expertise, students felt they could come up with better search terms and understand materials more cohesively when they queried basic/non-legal tools on a topic.

Most Significant Limitations:

Limited depth of analysis (23 students).

No tool provided results that went to the level of detail they were able to do themselves and felt comfortable sharing with a more experienced or senior attorney.

Citation and case law issues (22 students).

No tool was able to cite and/or Bluebook in an adaptive way. Some tools cited real case names, but incorrect citations, or summarized correct precedent but incorrect quotes or citations within the case.

Accuracy concerns (19 students).

Students were always worried about whether tools were overstating or fabricating details, beyond fake cases or citations. Students felt they needed to check and double check any output, even from tools they identified as being more reliable or grounded in “real” sources.

Hallucinations/fabrications (15 students).

Students were aware of and hypersensitive to hallucinated materials. They were worried about providing materials that were incorrect or overstated a position, especially when it came to primary law citations.

Jurisdiction-specific limitations (12 students).

Certain tools performed better in different jurisdictions. It wasn’t always clear if the results generated were because of a jurisdiction didn’t have good/sufficient/existing law on a topic or if the tool didn’t have access to materials for that jurisdiction.

Stay tuned for a class that speaks directly to this that my VAILL collaborator, Kyle Turner, and I have ready for Spring 2026. We’re calling it “Law Practice Simulation” — creative, right? Shoot me an email if you’re interested to see what we’re planning before the class launches.

In fact, this did happen with our very first in-class activity, which confirmed to me that I wanted students to ultimately experiment independently. Students who didn’t feel as comfortable with their AI knowledge took a backseat to the more knowledgeable students. They didn’t feel confident speaking up about their ideas, and, in one group, they didn’t feel comfortable pointing out that the group’s results included hallucinated cases, because they assumed the more experienced students were aware. Good reminder to all of us in the profession: it doesn’t matter who makes the mistake, we all share responsibility. Speak up!

And by this I mean, I researched them all myself without any AI help and got a general idea of the basics for the topic and/or jurisdiction. A very rigorous evaluation, clearly.